From Bootmakers to Gunshots

John Holding bordered a ship in Liverpool in the early years of the 1880’s along with his young family, surely with the giddy images of the new world flitting through his mind. But what brought him to leave behind the land of his birth?

Shropshire at this time was experiencing a ‘depression’ of sorts with prolonged spells of wet weather ruining cereal crops across the county. Consequently a shift in agrarian practices saw farmers leaning away from tillage and towards livestock farming. This brought about an inevitably increase in the costs of any businesses using cereals, such as bread making, as it primary raw material. It is possible that the increased costs effected this income to such a level that a departure from England and a move to a more favourable settings was the only outcome. Obviously the lure of a life in an urban environment far removed from his country-side background would also have appealed to him as would the idea of boundless opportunities which may have seemed limitless. But what he could never comprehend the tragic circumstances that would hang over the family for a generation.

Boarding the boat on that fateful day was his wife of eight years Elizabeth, nee Wylde, along with their four children John Henry, Amy, Frederick and Etheldreda. The family had left England to begin a new life in Massachusetts where John promptly found himself returning to the skills learnt back in his fathers business. Initially in the City Directories for Boston, John was listed as a baker working out of Albany Street, but presumably this baking business didn’t take off as by 1885 he has reverted back to his other skill, that of shoe-making.

This change in business structure would appear to have been more of a success with John continuing in this trade up until 1892 by which time he had become a naturalised citizen. Furthermore another son, Frank, had been born. Around this period the family returned to England and Shropshire once again for reasons that are unclear. It would appear that a short return was not planned which could have involved for instance a parents death, and instead a full repatriation to England was planned. By the 1890’s Shropshire’s local landlords, in an attempt to alleviate effects of the past decade of depression had provided a temporary relief to tenants. This relief in many cases now became a lasting reduction in rents with grazing rates reduced by 15% while arable rates were reduced by as much as 20%. These recent changes in relief may certainly have persuaded John to leave the States and return home and it is clear that he considered himself a farmer at this stage. This is in fact the occupation that John lists for himself in a ship manifest showing travellers arriving into Boston in the summer of 1895.

Once again the family had returned to the States after a period of just 3 years and John resumed his shoe-making business, this time working from Pleasant Street in Suffolk. A relative calm now prevailed as John expanded his business over the next few years to include his son John Henry within a new company under the title ‘John Holding and Son- shoe and bootmakers’. In 1907 John seems to have left the business in the capable hands of his son John Henry and took a retirement of sorts and moved to the outskirts of Boston where he worked as a farmer in some capacity at Poplar Street. It was here that misfortune truly began for the family.

Etheldreda, the youngest daughter of John, was admitted to hospital with an abscessed appendix in mid August of that year. Within two weeks she would be dead having suffered an acute dilatation of the stomach and heart. This stretching of the linings of both organs was brought about by the appendix infection and this in turn effected blood flow to the heart. The rapid decline of the young lady would indicate that heart failure was the final cause of death.

The following year police were called to the home of Ethelreda’s older brother Frederick in Folsom Street. Inside they found his lifeless body – the result of a gunshot wound to the head, self-inflicted during an episode that was described as a moment of insanity.

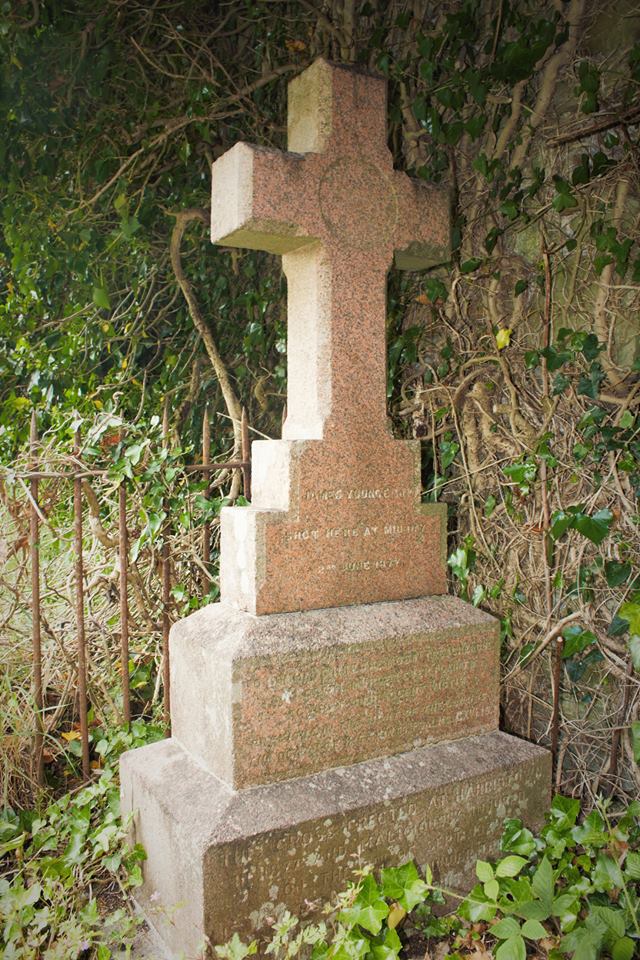

Burying his two children obviously affected John and Elizabeth greatly and in an attempt to escape this grief they moved further away from Boston with John even purchasing a farm in the suburbs of Canton where he employed Frank. But the tragic grip that death held on the family could not be escaped. 1911 saw John’s beloved wife Elizabeth pass away having suffered from Bright’s disease, or nephritis, for two years. This affliction involves a gradual inflammation of the kidneys, effecting the bodies ability to remove urea from it’s system. Over time the high levels of nitrogen causes uraemia which untreated can cause heart failure which was what Elizabeth died from ultimately. The psychological impact of this loss exacerbated that which had already befallen John, and just over a year later the police department were once again called to his residence with a similarly grim discovery awaiting the unfortunate policemen on duty. Like his son before him John had shot himself in the head with instant death the result. He was laid to rest alongside his wife Elizabeth and daughter Etheldreda at Hope cemetery.

With the loss of both of his parents Frank left the family farm and once again started working as a leather cutter closer to the city. In the intervening years he had lost his parents, and two older siblings. His other brother and sister John Henry and Amy were living and working in the central parts of the city with their families but he himself was alone in the world. If only he had married, he may have thought, on the balmy summer night in 1914, things may have been different. He mind may also have drifted back to the time over three decades previously when his family excitedly stepped onto the lands of America for the first time. Their innocent minds untainted as yet of the tragedy that would befall the family. Later that evening the neighbours heard a lone gunshot coming from Frank apartment as he became the family’s final victim of temporary insanity causing suicide.

References:

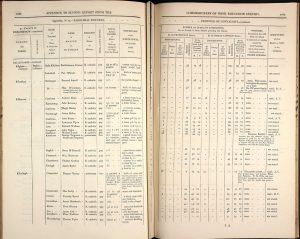

US and England Census Returns for the years 1871-1940

Boston City Directories

US Naturalization Records

Manchester passenger and crew records, 1820-1963

Massachusetts Death Records 1841-1915

R. Perren, ‘Effects of Agricultural. Depression on English. Estates of the Dukes of Sutherland, 1870-1900’ (Nottingham Univ. Ph.D. thesis, 1967)

D C Cox, J R Edwards, R C Hill, Ann J Kettle, R Perren, Trevor Rowley and P A Stamper, ‘Domesday Book: 1875-1985’, in A History of the County of Shropshire: Volume 4, Agriculture, ed. G C Baugh and C R Elrington (London, 1989 )