In the town land of Drishaghaun lies an ancient roughly cut flag of limestone that commemorates Fr Augustine Plunkett, “Fryer of Bellahaunes” who died in 1723. He was born in about 1670 probably in the Plunkett Castle that would lend it’s name to the village of Castleplunkett. Like many nobly born young men he joined the friars of St Augustine in Ballyhaunis where he devoted himself to the order for a time.

Unfortunately, for Plunkett, the relative religious stability in this country came to an abrupt end as Queen Anne came to the throne in England, bringing her intense devotion to the Anglican church with her. This devotion came with a great hatred of Roman Catholicism and saw a reign of persecution hit the churches and monasteries across the land. The abbey at Ballyhaunis was ravaged and Plunkett and his fellow friars were forced to flee. Refuge was sought in his home district where he set up a hospice in Rathmoyle for the sick and destitute.

The stone at Drishaghaun is said to mark the spot where he secretly administered to the faith of locals under the shade of a whitethorn tree, long gone but from which the local name for the monument arises – Crann a Leachta meaning A Tree of the Monument.

While there is no definitive evidence to suggest where Fr Augustine Plunkett is buried it is thought that he was laid to rest in Toberelva graveyard – a short distance from the family castle, where a number of Plunkett head stones from the early 18th century are visible.

Richard Luke Concanen, O.P. The First bishop of New York (1747-1810) sss

Richard Concanen was born in Kilbegnet in 1727 and from his youth knew that he was destined for the priesthood with a particular devotion to St. Dominic and his order. Unfortunately for Richard he was born into an age when religious oppression and penal laws forced Irish scholars preparing for the priesthood to seek education outside of the country.

The order itself had also suffered persecution with demolition of its monasteries, firstly by the Cromwellian invasion of the mid 1600’s followed by Queen Anne who extended the oppression into the 18th century. As a consequence the order relocated to the continent and to cities more welcoming to their teachings. Lisbon in Portugal, Rome in Italy and Louvain in Belgium all housed Dominican cloisters that were eminent centres of education. It was the Holy Cross in Louvain that Richard settled and here he received his religious habit in about 1765. At this time he also took the name Luke to add to that which he received at the time of his baptism.

Such was the promise shown that he was sent by his superiors to the Dominican House of Studies in Minerva and then on to San Clamente in Rome where he completed a four year study in Theology. Here he studied under many learned men including Fr. Thomas Troy, later Bishop of Ossory and Archbishop of Dublin.

He progressed through his studies rapidly and quickly made a name for himself amongst his contemporaries in the order but also amongst his congregations who eagerly gathered to hear the pulpit orator preaching fervently in their own tongue. He could now speak a number of language including English, Italian, Latin, French, German and coming from Galway the native tongue of his countrymen in Ireland.

Over the course of the following three decades, as his influence developed, Concanen was elevated to various prominent roles within the Dominican Order in Rome. Perhaps the most significant though occurred in about 1776 when his old mentor, Bishop Troy, appointed Concanen to act as his agent in Rome. Observing how effectively he took up this new role prelates from across Ireland, England and America followed suit and selected Concanen to also act on their capacity. This inevitably brought him to the forefront of Roman politics and into intimate contact with the Holy Father and the Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples, the committee responsible for the spread of the faith in non-Catholic countries.

He became a favourite of Pope Pius VI who duly appointed him Bishop of Kilmacduagh and Kilfenora, a position that Concanen was forced to refuse due to ill health and religious modesty.

Meanwhile across the Atlantic the first Catholic Bishop of the newly independent United States (later Archbishop of Baltimore), John Carroll, implored the Holy See in Rome for help in administering to the growing followers. Pope Pius VII’s solution in 1808 was to create several new dioceses in the country including that of New York and, on the advice of Archbishop Troy of Dublin, the bishopric was offered to Concanen. The position on this occasion was accepted.

He had for many years harboured a desire for a missionary role in the Americas but his duties in Rome had prevented this. Now as his health deteriorated a move away from the Gallic influences in Rome into the warm climate appealed greatly to the man. Regrettably Concanen never stepped foot on the American continent. Embargoes on Atlantic travel were in force due to the Napoleonic Wars and Concanen himself was detained in Naples while seeking passage to America. Bishop Concanen died of a fever in 1810 awaiting release and was buried in the Church of San Domenico, in this city.

Fr Edward J Flanagan of Ballymoe and Boys Town sss

Edward was born at Leabeg, outside Ballymoe, in 1886 to John and Honoria Flanagan, a couple of modest farmers with strong Catholic faith. His formative education was at the local Drimatemple national school before moving on to Summerhill College in Sligo where the Catholic teachings and ideology had a lasting impression on him. Upon leaving school and with a desire to enter the priesthood he made the decision to emigrate to America and to carry on his religious studies there. At the ave of 18 he arrived into New York where his education resumed before continuing in Italy and eventually Austria where he was ordained in 1912.

Returning home to the States he soon found himself serving in the parish of Omaha in Nebraska, where he was appalled by the destitution suffered by local young boys and felt he could help. In 1917 he founded his children home, on the outskirts of the town, where the care focused on treating the delinquencies of the boys with compassion instead of the usual prescribed corporal punishments. Through the work of the home young former at-risk boys who previously were inevitably caught in the loop of crime found they had a purpose in society. These revolutionary concepts were derided even by his superiors, but Fr Flanagan persevered with his ideals advocating a system of social preparation where the boys were taught to become responsible adults in addition to being given a trade.

Under his stewardship Boys Town, as it was soon named, grew steadily over the years to include all of the usual businesses and facilities that would be found in any town in America at the time. So much so that Boys Town was officially recognised as a village of the state of Nebraska in 1936

The innovative work of Fr Flanagan didn’t go unnoticed and in 1938 his life was celebrated in the Academy winning film ‘Boys Town’ starring Spencer Tracey with the script given the approval of Flanagan himself. Away from the silver screen his advice was sought for the foundation of many schemes similar to his across the globe and it was while attending one such event in Berlin that he died in 1948. He was returned to America and buried in his beloved Boys Town.

2001 saw a statue unveiled in Ballymoe commemorating Fr Flanagan and his achievements with an exact replica being placed in Boys Town, Nebraska a symbol of the two towns united in acclaiming their famous son.

Irish National Schools sss

The English Parliament in 1826 commissioned a report to investigate the state of district schools in Ireland. It was in fact only one of a number of such investigations that had taken place in the preceding decades that sought to tackle the terrible literacy and numeracy levels of the Irish. Each time the results were offered, debated and then rejected as parties with vested interests opposed any wholesale changes. The report on this occasion though was to have a more desirable and inclusive outcome.

Education, particularly Catholic education, in the country was profoundly affected by the Penal Laws of the previous century. These laws, in part, made it an offence to send a Catholic child to school or to be educated as one. This led to the illegal teaching of children in secret countryside locations known as hedge-schools, the name being more of an indication of the rural setting then the external aspect of the school. Instruction here varied greatly, depending on the capability and knowledge of the resident teacher, with some totally unsuited to the task. Formal training was impossible, leaving the sole route into teaching being in effect an apprenticeship with the local hedgemaster. Furthermore, a casual approach taken by families to education, when farming needs were of greater concern, meant that even the best teachers could never expect to receive adequate payments. Many were forced to live in squalor. Contemporary reports from the time show that in some instances, after lessons finished, teachers were forced to accompany a pupil to their home to receive food or shelter – in part payment for their fees.

At the start of the 19th century Protestant schools opened across the country offering free education for all, including the young Catholic children. In the absence of any state sponsored system these appeared to have filled the needs, but it was at great cost. With the free education came an inevitable religious influence on the children that caused great concern particularly to the families forced to send them there.

Daniel O’Connell, with the help of Prime Minister Arthur Wellesley, advocated for change and with The Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829 the landscape was transformed forever. With this Act laws were passed to address the problem of the existing religious biased education. Two years later The National School System was established that looked to create nation-wide standards in the educational structures. Among other things that was examined was the subjects taught, and a structure that paid teachers based on ability. A major and controversial sentiment also being that any schools seeking funding must be managed by joint Catholic and Protestant guardians. In the early years this proved successful but gradually, each religious group petitioned the government to allow grants to be given to schools under the care of individual churches. This pressure was so effective that in the next 30 years the numbers of schools under joint management had dropped to just 4%.

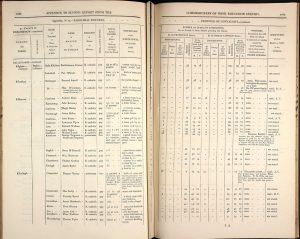

The 1826 report covered the whole of the country and included the schools name, schoolmaster or mistress, wages paid and the number of students attending. Of particular interest though may be the description of the sometimes hovel-like buildings that were the common places of education in the years leading up to the famine in Ireland.

FINNNN

Ballenagare House sss

Following the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland on the mid 17th century many lands of former great Catholic families were confiscated and handed to Protestant settlers. The O’Connor family, who through all adversity had always retained a Catholic faith, were inevitably in Cromwell’s firing line. Their property, lands and power were all taken leaving them literally destitute for a generation.

It was only through the courts in 1720 that Denis O’Connor found justice with a moderate proportion of their ancestral lands restored – including that of Ballenagare. Here he built the modest Ballenagare House which became a meeting point for Catholic families in the area as well as the famed blind bard Turlough O’Carolan. O’Carolan’s harp can nowadays be found at Clonalis House, the ancestral home of The O’Conor Don and home to the direct descendants of Rory O’Conor – the last high king of Ireland.