The stone dated 1841 comes from the original workhouse structure that was built around this time on a six acre site south of Castlerea town. Constructed using the design laid down by Poor Law Commissioner architect George Wilkinson it was one that was repeated to a great extent across the country as places to house the growing destitute Irish. Long thought lost to history the stone was located in recent times and enclosed by a local mason into a standing stone structure on the site of Bully’s Acre in Knockroe. (This term has been used regularly to describe famine or workhouse mass graves with the origin possibly stemming from the Irish word “buile” which can be used to describe someone who is insane)

Initially built to accommodate 1000 paupers the Union Workhouse was completed in 1842 but long running financial issues meant it would be four years until it was finally used to receive the poverty stricken. Running costs for the complex were dependant on the collection of Poor Rates from local landholders but as the famine gripped the country they were less inclined to pay causing lengthy delays and postponements. Furthermore the original cost of rates were set before the famine years and were later seen to be inadequate especially as inmate numbers exceeded capacity.

It was into this environment that the workhouse finally opened it’s doors to the starving masses waiting outside. Quickly the numbers became unbearable with the paupers huddled together in dormitories that became a breeding ground for disease, hunger and death.

Once inside inmates were separated from their families, often not seeing them again, with those that were capable being given menial manual jobs for the sustenance that they would receive. Men were tasked with breaking stones in the workhouse yard which were to be used as gravel for the many pointless famine roads being built while woman regularly worked at domestic duties and caring for the sick indoors. Even the older inmates were put to work with many mending clothes, spinning wool or picking oakum.

The work available however could never cope with the sheer numbers of destitute hungry and for many who entered the workhouse in Castlerea they would not leave alive.

Reports from the period describe in harrowing detail how when a person was near to death they were moved to an area at the rear of the building called the black room. Here they were allowed to die before their corpse was lowered from the window into a vast pit where it was covered with lime.

Details of the exact number of deaths at the workhouse and subsequent burials in Bully’s Acre are unclear but considering that Castlerea and Roscommon as a whole suffered such widespread losses during the famine years the figure is undoubtedly high.

During the Great Famine the population of Roscommon was particularly badly impacted with a population loss of 31% making it the worst hit county in the country

Irish National Schools sss

The English Parliament in 1826 commissioned a report to investigate the state of district schools in Ireland. It was in fact only one of a number of such investigations that had taken place in the preceding decades that sought to tackle the terrible literacy and numeracy levels of the Irish. Each time the results were offered, debated and then rejected as parties with vested interests opposed any wholesale changes. The report on this occasion though was to have a more desirable and inclusive outcome.

Education, particularly Catholic education, in the country was profoundly affected by the Penal Laws of the previous century. These laws, in part, made it an offence to send a Catholic child to school or to be educated as one. This led to the illegal teaching of children in secret countryside locations known as hedge-schools, the name being more of an indication of the rural setting then the external aspect of the school. Instruction here varied greatly, depending on the capability and knowledge of the resident teacher, with some totally unsuited to the task. Formal training was impossible, leaving the sole route into teaching being in effect an apprenticeship with the local hedgemaster. Furthermore, a casual approach taken by families to education, when farming needs were of greater concern, meant that even the best teachers could never expect to receive adequate payments. Many were forced to live in squalor. Contemporary reports from the time show that in some instances, after lessons finished, teachers were forced to accompany a pupil to their home to receive food or shelter – in part payment for their fees.

At the start of the 19th century Protestant schools opened across the country offering free education for all, including the young Catholic children. In the absence of any state sponsored system these appeared to have filled the needs, but it was at great cost. With the free education came an inevitable religious influence on the children that caused great concern particularly to the families forced to send them there.

Daniel O’Connell, with the help of Prime Minister Arthur Wellesley, advocated for change and with The Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829 the landscape was transformed forever. With this Act laws were passed to address the problem of the existing religious biased education. Two years later The National School System was established that looked to create nation-wide standards in the educational structures. Among other things that was examined was the subjects taught, and a structure that paid teachers based on ability. A major and controversial sentiment also being that any schools seeking funding must be managed by joint Catholic and Protestant guardians. In the early years this proved successful but gradually, each religious group petitioned the government to allow grants to be given to schools under the care of individual churches. This pressure was so effective that in the next 30 years the numbers of schools under joint management had dropped to just 4%.

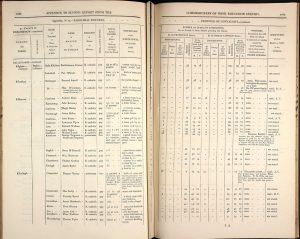

The 1826 report covered the whole of the country and included the schools name, schoolmaster or mistress, wages paid and the number of students attending. Of particular interest though may be the description of the sometimes hovel-like buildings that were the common places of education in the years leading up to the famine in Ireland.

FINNNN